I love games. I learn from them. They help me connect with the world around me. In short, they make me a better person.

Each of us has memories associated with games, memories that don’t fade. Learning to play gin rummy or solitaire from a grandparent. It was in quiet times like this, when my grandparents were watching me as a child, that I learned about intergenerational relationships and roots. Playing hide and seek or tag (for us it was a tag variation we called run around the cellar door) with neighbors and cousins. As an awkward, uncoordinated kid, games like this helped me understand that mental skills were just as important as physical skills. The informal, unsupervised play gave us the opportunity to resolve disputes on our own and to establish systems for working together, even when we were working in opposition. Sports in high school often involved brutal and explosive confrontations, ending up with more than a couple of trips to the ER. But, it developed my persistence, it fostered my sense of cooperation, it taught me the value of preparation, and I learned how to move past failure.

Each of us has memories associated with games, memories that don’t fade. Learning to play gin rummy or solitaire from a grandparent. It was in quiet times like this, when my grandparents were watching me as a child, that I learned about intergenerational relationships and roots. Playing hide and seek or tag (for us it was a tag variation we called run around the cellar door) with neighbors and cousins. As an awkward, uncoordinated kid, games like this helped me understand that mental skills were just as important as physical skills. The informal, unsupervised play gave us the opportunity to resolve disputes on our own and to establish systems for working together, even when we were working in opposition. Sports in high school often involved brutal and explosive confrontations, ending up with more than a couple of trips to the ER. But, it developed my persistence, it fostered my sense of cooperation, it taught me the value of preparation, and I learned how to move past failure.

Yet, the best games also stimulated my imagination by drawing me into a story. It might be as simple (and pedantic) as a board game like The Game of Life in which the objectives of the game are dressed in a fictitious—yet commonplace—adult experience. By making the fictitious, adult experience more removed from the everyday, like in Monopoly, players immerse themselves even more into the story of the game, actually feeling as if they own the properties. The more interactive the storytelling, the more immersive the experience becomes.

Yet, the best games also stimulated my imagination by drawing me into a story. It might be as simple (and pedantic) as a board game like The Game of Life in which the objectives of the game are dressed in a fictitious—yet commonplace—adult experience. By making the fictitious, adult experience more removed from the everyday, like in Monopoly, players immerse themselves even more into the story of the game, actually feeling as if they own the properties. The more interactive the storytelling, the more immersive the experience becomes.

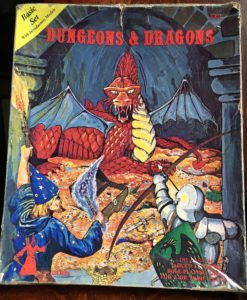

In the Fall of 1978, my parents gave me Dungeons & Dragons. I still play it today. And, while it may undermine my geek cred, I did not open the box and begin playing immediately, never putting it down over the last four decades. I was the first of my friends to get it and there was nobody that I knew who could teach it to me. I learned and my friends learned, and we taught each other. We persisted, because we were already immersed in Tolkien’s world of adventure and imagination and D&D was an opportunity to make those worlds our own. The stories drew us into the game. Then the richness of the game drew us into other stories, including stories of our own creation.

In the Fall of 1978, my parents gave me Dungeons & Dragons. I still play it today. And, while it may undermine my geek cred, I did not open the box and begin playing immediately, never putting it down over the last four decades. I was the first of my friends to get it and there was nobody that I knew who could teach it to me. I learned and my friends learned, and we taught each other. We persisted, because we were already immersed in Tolkien’s world of adventure and imagination and D&D was an opportunity to make those worlds our own. The stories drew us into the game. Then the richness of the game drew us into other stories, including stories of our own creation.

Similarly, when I first introduced my sons to the game, there was a learning curve that got in the way. I have three boys and they are each about five years apart in age. The game takes time—and preparation—and at the time, we were looking for multi-age activities because time between other scheduled activities was limited and we were all together. But, when the oldest was just old enough to play, his younger brothers were too young. When my middle son was old enough to start learning to play, I had begun presenting at pop culture conventions on legal issues around comics and games. Bringing him along introduced all of us to convention gaming and a world in which people volunteered their time to teach you games and in which people of all different backgrounds and ages came together to play and create a story.

It was at one of those conventions that I met Eric Thomas. He was the president of an indie game publisher at the time and had created a fantasy role-playing game that was relatively easy to learn and his writing and play style encouraged a campy, open approach that immediately welcomed all players. The game, and Eric, had a minor cult following in the area, and my kids—from ages sixteen to six—and I loved it. Ease of play and easy learning were things that opened up the world of gaming for our family.

Gainsage is our effort to bring that experience to folks outside of gaming conventions.