We launched our first game!

For a limited time, if you sign up to receive our Gainsage Newsletter (either through the link in the footer or on our Home page) you’ll get a coupon for a free digital copy. There are also additional free resources to support game play in our Gainsage Toy Chest. We’ll add to these as we create more.

It is called Diecast Demolition: The Game of Toy Car Destruction. It reminds me of my Dad. Not so much because the game involves cars (or even that my Dad had a particular interest in cars), but because the game encourages making cars and offers way more opportunities to discuss math and physics than a kid really wants to have (not that you have to have them, its just nice to know that they are there).

First, I should explain that this game is our entry into tabletop, car combat games. These games include Osprey Publishing‘s relatively recent, award-winning Gaslands, which encourages decorating diecast, toy cars to look like the combat vehicle you drive in a post-apocalyptic landscape. Before that, and through multiple editions, Steve Jackson Games put out Car Wars, which in some incarnations relied on smaller scale car templates or tokens instead of toy cars.

Our game fits within this genre. Set in the near future, it opts for a simplified, somewhat more kid friendly setting of arena combat between robot drivers. Picture an environment in which the risk of injuries from increasingly spectacular, athletic competitions runs into BattleBots-like, technology-driven confrontations. The engineers are the heroes and they all live to fight another day. It also opts for a streamlined rules system (the basic game can be printed on four pieces of paper), random car generation, and some six-sided dice. But, perhaps what makes this easy-to-learn, easy-to-play game stand out, is that a standard ruler and protractor replace custom movement templates or grid mats.

How I came to learn from creative conflict.

When I was growing up, I didn’t realize how lucky I was to have a father who was an engineer. I resented working on math or science homework with him. I hated the fact that it seemed to take longer than necessary to get the answer right because there was always a greater meaning or more fundamental lesson hidden in my algebra. But, when it came to making something from a pile of scraps, he was the best. And, the math and science lessons hidden in those projects have stayed with me to this day. Bernoulli’s Principle was involved in trying to make my boomerang be the best. (If you really want to dig into boomerangs and physics, check this out.) Newton’s Third Law of Motion is what made my model rockets launch (cool explanation and nice link for wheeled rocket racer lesson is here). The secret behind learning without realizing it is engagement and agency. When I have a set of math problems assigned for the abstract purpose of learning math, I am not engaged in the activity; and, without that engagement, someone is pushing knowledge toward me, rather than me pulling on its thread.

The first time my father and I made a wooden competition car for my youth group (the first was YMCA’s Indian Guides, later efforts were with the Cub Scouts Pinewood Derby), it ended in tears. In second grade, I was too young to work the power tools and I didn’t understand the mechanics behind these gravity propelled vehicles. In my mind, we were building Speed Racer’s Mach V, we ended up with a very functional tear drop. When my Dad tried to explain to me that the design worked on the same principle as a bobsled, I didn’t care. It was too late. Instead of starting with my interest and providing the support for me to learn how to make it faster; we were starting with the lesson and discussing where I might want to take it.

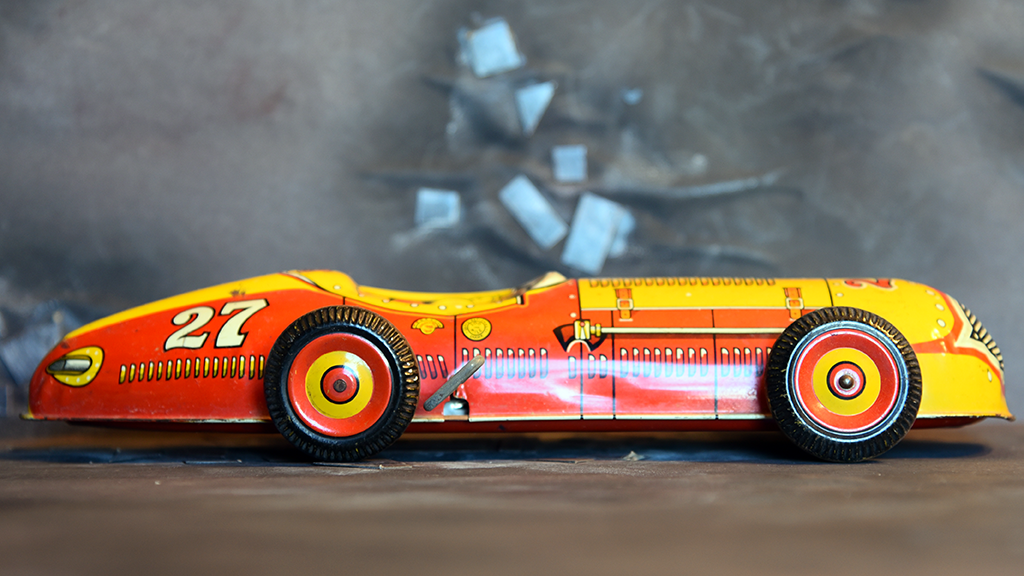

I no longer have that car. I think that I destroyed it in a tantrum. But, my Dad and I learned to work together on other projects. I have an old metal wind-up car from his childhood and its sleek teardrop shape reminds me about the lesson he was trying to impart. I also have a wooden car body that he carved for himself when we were working on my last Pinewood Derby as a Webelos. He leaned in to the symbolism of our shared activity and I see it as a an example of form over function. It reminds me that why we learn something is as important as what we learn.

Diecast Demolition has many opportunities for learning. Movement is based on vectors for straight lines, and arcs for turns. Vectors require basic skills using a ruler to measure distance in inches and arcs require basic skills using a protractor to measure an angle. Game tactics encourage estimation and spatial reasoning. But, the game is not about learning. It is about having fun and being goofy. It’s about creating a simple narrative in which we control the story. We control how the cars look and how they behave. We don’t play the game to learn Euclidean geometry or to learn how to measure. We learn how to measure, so we can pull off the “Malachi Crunch,” and thus remember the tragic love between Pinky Tuscadero and The Fonz.

And that’s a lesson that lasts a lifetime.